A profit-first framework for Amazon sellers who want efficiency without silently capping long-term growth.

Most Amazon brands use negative keywords like a cleanup crew, cutting queries the moment ROAS dips. And that’s exactly how they cap their own growth. They treat Amazon negative keywords as the bouncers for their ad campaigns, a simple way to stop bleeding ad spend on shoppers who aren’t looking for what they sell. While that feels like taking control, it’s a high-stakes, irreversible decision at scale.

Block a query before diagnosing it, and you’re not improving efficiency—you’re deleting market intelligence. This guide explains when negatives are a strategic lever to protect profit and when they’re a blunt instrument that hides bigger, more critical problems.

Book Your ROI Forecast — See where your growth is actually capped.

At-a-Glance — Amazon Negative Keywords for Operators

Table of Contents

For busy decision-makers, here’s the bottom line on what really matters when it comes to an Amazon negative keyword strategy:

-

Negatives don’t fix low CVR. A low conversion rate often signals a problem with your listing, price, or offer—not a bad keyword. Blocking the query just masks the root cause.

-

Query intent matters more than match type. Understanding why a customer is searching is far more valuable than simply blocking a word. Is it a true mismatch or a signal of an unmet need?

-

Over-blocking caps scale quietly. Aggressively adding negative keywords can create an invisible ceiling on your growth, preventing you from discovering new long-tail keywords and customer segments.

-

Most waste comes from pricing + listing gaps, not keywords. The biggest drains on your ad budget are rarely individual keywords. They’re usually systemic issues like uncompetitive pricing (see our guide on Amazon dynamic pricing strategies), poor listing quality, or inventory gaps that kill conversion momentum.

What Amazon Negative Keywords Actually Do

Think of a negative keyword less like tweaking a bid and more like flipping a hard “off” switch. When you add one, you give Amazon’s algorithm a permanent, non-negotiable directive: “For this specific search, my ad does not exist.”

This rule applies at the campaign or ad group level, creating a digital dead zone where your ad is completely invisible to a particular set of shoppers. Amazon treats these commands aggressively because they’re designed to give you absolute control over where your ad spend doesn’t go. This finality is why they’re so powerful for cutting waste, but also incredibly dangerous if you get too aggressive.

Negative Exact vs. Negative Phrase

-

Negative Exact: This is your surgical scalpel. It removes one single, specific search query. Add

[men's winter boots]as a negative exact match, and your ad can still show for “waterproof men’s winter boots.” It eliminates a diagnosed problem without collateral damage. -

Negative Phrase: This is a much wider net. It blocks any search query containing your negative phrase in that exact order. Negativizing

"winter boots"blocks everything from “men’s winter boots” to “insulated black winter boots,” potentially wiping out dozens of relevant long-tail searches.

Why Most Brands Overuse Negative Keywords

Most brands treat their negative keywords list like a digital junk drawer, tossing in any search term that doesn’t immediately convert. It feels productive, but it’s a classic case of treating the symptom, not the disease. You’re not just cutting wasted spend; you’re severing ties to valuable market data and masking deeper operational flaws. This reactive “cleanup” creates three distinct failure patterns that quietly stall growth.

Using Negatives to Mask Conversion Problems

When a query gets clicks but no sales, the knee-jerk reaction is to add it as a negative. But this move sidesteps the most critical question: why isn’t it converting? Low CVR is rarely a bad query; it’s often a listing or offer mismatch. The real culprit is frequently a disconnect between what the shopper expected and what they found on your product detail page: a pricing mismatch, weak images, or an uncompetitive offer. Blocking the keyword is a critical error; you’re destroying a data point that was trying to tell you something was broken.

Premature “Efficiency Cleanup”

The second trap is the premature push for efficiency. A brand gets hyper-focused on boosting ROAS, so they aggressively add any non-converting term. On paper, the metrics look great—ACoS drops and ROAS climbs. But look closer, and total profit has often stagnated. This happens because the “cleanup” eliminated higher-incrementality traffic. You improved efficiency but reduced net new demand. You’ve optimized yourself into a smaller circle, sacrificing real volume for a vanity metric.

Loss of Long-Tail Demand

The most insidious damage comes from suppressing long-tail demand, especially with negative phrase match. A single broad negative can inadvertently block hundreds of highly specific, purchase-ready search queries you never knew existed.

For example, a brand selling high-end “leather messenger bags” might negativize the word “cheap.” In doing so, they could block a profitable query like “best work bag under $100 that isn’t cheap plastic.”

We break down this psychology inside our Amazon anchor pricing strategy guide, and why pricing perception often matters more than the keyword itself.

This cumulative loss of query diversity quietly puts a hard ceiling on your account’s ability to scale.

When Negative Keywords Do Make Sense

Amazon doesn’t reward activity. It rewards control. Negative keywords are powerful—if you know when not to use them. Negative keywords are a critical lever for protecting profit, but only when you’re applying them to a clearly diagnosed problem. Their job isn’t cleanup. It’s governance.

Negatives should follow query diagnosis—not replace it.

True Irrelevant Intent

This is the most clear-cut reason to use a negative keyword. We’re talking about blocking traffic that is genuinely, fundamentally irrelevant. If you sell premium leather dog collars, you have zero business paying for clicks from searches like “shock collar” or “cat collar.” These are black-and-white cases of wasted ad spend. Adding these terms as negatives is essential housekeeping.

Margin-Protecting Exclusions

Not all conversions are good conversions. For SKUs with razor-thin margins, there’s a hard profitability floor. Spend one penny over a certain ACoS, and you are guaranteed to lose money on that sale. In these cases, negative keywords become a P&L decision. If a broad search term is constantly funneling traffic to a low-margin SKU and the ACoS is deep in the red, you have to block it to protect overall profitability.

Proven Cannibalization Control

Sometimes, a broad match keyword in your non-branded campaign starts pulling in clicks from your branded searches. This is “cannibalization,” and it inflates ACoS and muddies your data. When you have diagnosed this overlap—not just assumed it—negative keywords are the fix. By adding your brand terms as negative exact matches to non-branded campaigns, you force that traffic to flow where it belongs.

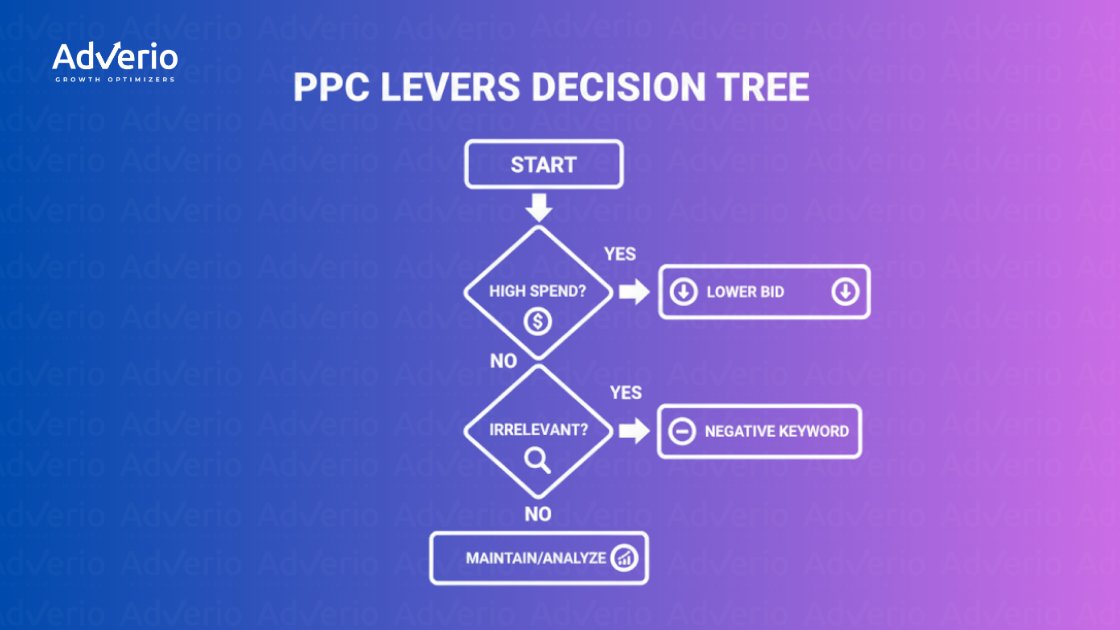

Negative Keywords vs Other Control Levers

Relying on negative keywords for everything is like trying to steer a plane using only the rudder. Real control comes from understanding the whole spectrum of levers and knowing when to pull each one. A reactive operator uses a permanent solution (a negative keyword) for what might be a temporary problem. The trick is to weigh the precision of each control against its potential impact on future discovery and sales volume.

| Control Lever | Control Precision | Risk to Scale | Best Use Case | Common Misuse |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Keywords | High & Permanent | High | Permanently blocking diagnosed irrelevant or unprofitable traffic. | Masking low CVR, premature “efficiency” cleanup, blocking discovery keywords. Often, brands should test structured discounting instead (see our breakdown of Coupons vs Best Deals vs Lightning Deals on Amazon) before permanently blocking demand. |

| Bids | High & Flexible | Low to Medium | Managing cost-per-click and profitability on a granular, keyword-by-keyword basis. | Lowering bids on all poor performers instead of diagnosing the root cause. |

| Budget Caps | Low & Broad | High | Capping total daily or campaign spend to control a fixed advertising budget. | Using budget caps to control ACoS instead of using more precise levers like bids. |

| Placement Modifiers | Medium & Specific | Low | Optimizing spend based on ad placement performance (e.g., top-of-search, product pages). | Applying blanket modifiers without analyzing placement-specific conversion data. |

How Adverio Governs Negative Keywords Without Killing Growth

Negative keywords aren’t an optimization tactic. They’re a governance decision.

We take negative match types seriously, so seriously that in 2026, Adverio was recognized with the AdLabs “Big Negator” Award for strategic negative keyword governance.

Why? Because most brands use negatives to hide inefficiency. We use them to protect profit.

When applied correctly, negative keywords aren’t just defensive — they’re a precision tool to stop lighting ad dollars on fire while preserving incremental growth.

Inside Adverio’s Growth Cultivator framework, negatives sit at the intersection of:

-

Profit-Driven Catalog Optimization

-

Intelligent Growth Marketing

-

Marketplace Conversion Rate Optimization

Before we block demand, we audit:

-

Incrementality (Is this new-to-brand traffic?)

-

Market Share Funnel shifts (Impression → Click → ATC → Purchase)

-

Listing Quality Score (LQS)

-

Pricing elasticity and badge impact

-

Inventory depth + Buy Box stability

If the constraint is traffic quality → we block.

If the constraint is offer weakness → we fix the PDP.

If the constraint is pricing → we govern pricing.

That’s the difference between optimizing ads… and governing growth.

👉 Book Your ROI Forecast

How Adverio Diagnoses Before Adding Negatives

Inside our Amazon PPC Management services, we treat negatives as a surgical tool—not a shortcut. You don’t head into surgery without a full diagnosis. Before we even think about blocking a search term, we put it through a multi-point analysis to uncover the real reason for underperformance.

-

Search Term → SKU Mapping: We map the exact search term to the specific SKU that got the click. A single query can perform wildly differently across your catalog. Without this mapping, you risk blocking a valuable query just because it performed poorly for the wrong product.

-

CVR by Query vs. Category Median: We check the query’s conversion rate (CVR) against the category median. A low CVR isn’t automatically a red flag. If a query converts at 5% while the category average is 15%, something’s broken. But if it converts at 5% and the category average is 3%, it’s an outperformer.

-

Price Alignment: Is the product’s price aligned with what the shopper was looking for? If someone searches “budget option,” are they landing on your premium-priced product? This is an offer problem, not a keyword problem.

-

Listing Relevance (LQS): If a shopper searches for “waterproof,” is that feature buried in the fifth bullet point instead of being front and center? Fixing the listing is the right move here, not blocking the traffic.

-

Incrementality Risk: We weigh the immediate “efficiency” gain against the potential long-term loss of market share. It’s only after a search term fails this entire audit that we’ll consider making it a negative. It’s a governed process, not a guessing game.

We also analyze directional shifts in the market share funnel:

Impression Share → Click Share → Add-to-Cart Share → Purchase Share.

If add-to-carts rise but purchases stall, the issue isn’t the keyword—it’s the offer.

How Adverio Helps Prevent “Over-Negativing” Accounts

When advertising is treated as a separate function, the only tool you have for a low-converting search term is a negative keyword. This fragmented approach puts a hard cap on growth.

At Adverio, we prevent this by governing ads alongside the other critical pillars: listings, pricing, and inventory. This integrated system lets us solve the root cause of poor performance instead of just papering over the symptoms. A core part of our comprehensive Amazon account management involves systematically reviewing—and often rolling back—previously implemented negatives once a proper diagnosis shows a listing or pricing issue was the real culprit.

Instead of just chasing a cosmetic ROAS improvement that hides bigger operational issues, our focus is squarely on driving total, sustainable profit growth.

FAQs

Do negative keywords hurt Amazon sales?

Yes—especially when they eliminate incremental traffic and leave you over-reliant on branded demand capture. The quickest way to hurt sales is by over-blocking with broad or phrase match negatives. This quietly puts a permanent cap on your growth potential, suppressing demand for new products before you even know it exists.

When should you add negative keywords on Amazon?

Only after a thorough diagnosis proves it’s necessary. Add a negative keyword only when a search term is completely irrelevant, guaranteed to be unprofitable, or causing proven ad spend cannibalization between campaigns.

Can negative keywords block profitable searches?

Absolutely. This happens constantly with negative phrase match. A single, seemingly logical negative can wipe out dozens of profitable, specific search queries. For example, blocking “school backpack” could also block a high-converting search for a “durable, waterproof backpack for law school.”

Negative phrase vs exact — which is safer?

Negative exact is dramatically safer. Think of it as a surgical scalpel that removes only a specific query. Negative phrase is a wider net that carries a much higher risk of unintentionally scooping up relevant, long-tail traffic. Use it with extreme caution.

Should you automate negative keywords?

Automating negatives without a sophisticated diagnostic system is incredibly risky. Most tools use simplistic rules that lead to the exact over-negating behavior that kills growth. Without intelligence that analyzes CVR, listing quality, and pricing context, a manual, diagnosis-driven approach is always the safer path.